In July 2005, at age twenty-four, I quit my job and moved from New York to Utah to ski at Snowbird, a resort about thirty miles southeast of Salt Lake City. My lifestyle, however, didn’t fit the ski-bum archetype. During the ski season, I attended graduate school full-time at the University of Utah and lived on campus in a student apartment. I was just a regular guy living a regular life (as a student) while skiing some of the best snow and inbounds terrain in the United States.

After every ski day that season, I published a report on my website. While rereading those entries in late 2017, I felt detached from the experiences I had described. The passage of time allowed me to read the entries more objectively, and I enjoyed them for more than their nostalgic value. I thought other skiers might also find the entries compelling. In January 2018, I began compiling them into this book.

Stories in the skiing media often feature extreme terrain, impractical skiing-centric lifestyles, and easy access to seemingly endless fresh powder. This is not one of those stories. Instead, my story features terrain accessible to any skier with a lift ticket, a skiing lifestyle tempered by school or work obligations, and fresh tracks obtained through luck and persistence, not by being given privileged access.

I hope my story demonstrates what it took for an ordinary skier like me to explore a mountain and find the fleeting moments that make skiing special. I hope you can identify with the doubts and challenges I faced before, during, and after that season. Most of all, I hope my story leaves you feeling more excited about skiing.

Patience was not a virtue present in the tram line this morning. People were cutting in front of Brendan and me until I adopted a defensive stance using my poles. A gaggle of malcontents complained when the line didn’t start moving at the stroke of nine (the tram’s opening time). A few minutes later, a veritable riot broke out when the tram line ticket checker let a group of instructors and their clients through the turnstiles instead of the public. The malcontents heckled her until she started the public line moving again.

It has snowed for eleven straight days and seventeen of the last nineteen. About a hundred inches of snow has fallen at Snowbird since March 3, including a foot last night. At less than 5 percent water content, the new snow was about as light as it gets.

Given the new snow and our limited availability (Brendan and I both had to leave at noon), there would be no warm-up run today. We headed to Primrose Path. The light was flat and gray, and the visibility was maybe a hundred feet. Primrose was mostly untracked, but the wind had drifted the snow into heaps that were the deepest I had ever encountered on skis. I took a few cautious turns to find my balance before I opened the throttle and skied through the nearly waist-deep powder with gusto. The snow was so deep that I couldn’t get enough speed, despite pointing my skis straight down the fall line. I fell twice when my skis started submarining without ever finding the bottom. Those falls were almost as fun as the skiing.

Farther down the mountain, Anderson’s Hill was also mostly untracked. Anderson’s had a bit less snow and none of the drifts. I maintained the speed necessary to stay afloat in the powder better there. The conditions on Phone 3 Shot were also superb. Snowbird had served up powder face shots from top to bottom.

Powder days already have a mystique, but today’s variable weather amplified it. Snow was falling, but the sun would occasionally peek through breaks in the clouds. In those moments, the sun would illuminate the crystalline snowflakes, transforming a flatly lit, two-dimensional scene into three dimensions and making it appear as if we were skiing inside a shaken snow globe. Then the clouds would close up again, and it was back to flat light.

Despite the frenetic skiing activity, there was a pervasive stillness about the mountain, like a busy public library—quiet yet hectic. On most normal days, ski and snowboard edges loudly scratch against the snow surface. Today, they were silent. The only persistent sounds were the skiers’ whoops and hollers and the gentle rustling caused by snow billowing up against my ski jacket. The concussive blasts of avalanche-control bombs and their roiling echoes throughout the canyon also occasionally broke the silence.

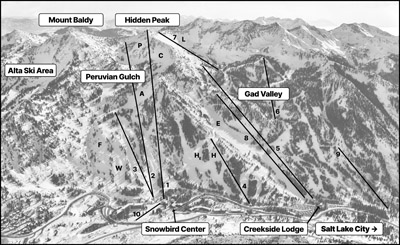

The snow on the lower mountain was almost as good as up top. We skied laps off the Peruvian lift rather than wait in line for the tram. The sacrifice in vertical footage and terrain variety allowed us to squeeze in more runs during our limited time available. We skied Phone 3 Shot repeatedly during our Peruvian laps. Although short, that trail’s steep, consistent fall line and wind-loaded powder made it a better option than the adjacent Chip’s Face. Every Phone 3 run we skied was good.

The tram line was still long at around 11 a.m., but we weren’t going to leave without taking at least one more tram run.

This time, we followed the Cirque Traverse down to the Lower Cirque. We skied along the ridge, surveying the wide-open, powder-filled bowl. Any line I picked was going to be good. I dropped in and quickly found a good rhythm. I maintained enough speed to stay on top of the snow better than I had on Primrose earlier in the day, but I still got face shots the entire run. That run was a contender for my favorite ever.

It was almost noon when we skied onto Snowbird Center’s Plaza Deck, but we got back in line for one last tram run. Alas, my last run of the day wasn’t as good as the prior one. It was well past noon when we finished. We had to leave.

Life rarely feels dreamlike in the moment. With time, nostalgia polishes the jagged edges of our lived experiences into memories that more closely resemble dreams. But today was special. I felt like I was living my old daydreams of skiing Snowbird. We found deep, light powder snow everywhere we skied. Brendan quipped that he could hear Warren Miller narrating his turns. We felt like the stars of our own ski movie today.

After skiing, I showered and hustled to a computer lab on the University of Utah’s campus to work on a group project. My cheeks were still flushed from the earlier onslaught of snow, cold, and wind. The magnanimity generated by a ski day that hit all the right notes smoothed the tedium of the group work into something more tolerable.

Throughout the rest of the day, I felt like I was still floating through powder. It’s not unusual for people to feel illusions of self-motion—usually described as rocking, bobbing, or swaying—after exposure to sustained motion, such as those experienced on an ocean cruise or airplane flight. I had felt those sensations after powder days before, but today, they were more palpable than ever.

Rating: ★★★★★